EARLY ON, I NEVER WROTE ABOUT maple syrup because I was afraid of being pegged as a New England food writer, and I never got around to maple until now. (I did publish a couple of maple recipes, including the one at the end of this post.) But maple syrup is a really good subject. The taste varies from sugarbush to sugarbush and boiling to boiling. People point to the soil, the angle toward the sun, the weather that spring, the moment during the season, and the knowledge and equipment of the producer. In some years and locations, a maker gets mostly light-colored syrup, but generally as the season advances, the syrup grows darker and stronger.

Each producing state and province, with Quebec making about 70 percent of the world total, used to set its own maple grades, but since 2015 all the grades have been the same. There are just two, Grade A and everything else, which isn’t for retail sale and is called Processing Grade. To lump all the good syrup together as Grade A is pure marketing. Grade A, however, is divided by color into Golden, Amber, Dark, or Very Dark, and the syrup must meet standards for clarity, density, and flavor. Previous generations preferred the lightest syrup, which in Vermont used to be called “Fancy.” The farmer-producers originally made sugar not syrup, and maybe they liked the lighter flavor because it was closer to the neutral sweetness of white sugar, which was expensive and had to be bought. The flavor of the lightest syrup is certainly delicate, but it’s also more complex. I like Amber, which has some of the qualities of both light and dark. Consumers, however, increasingly opt for Dark and Very Dark.

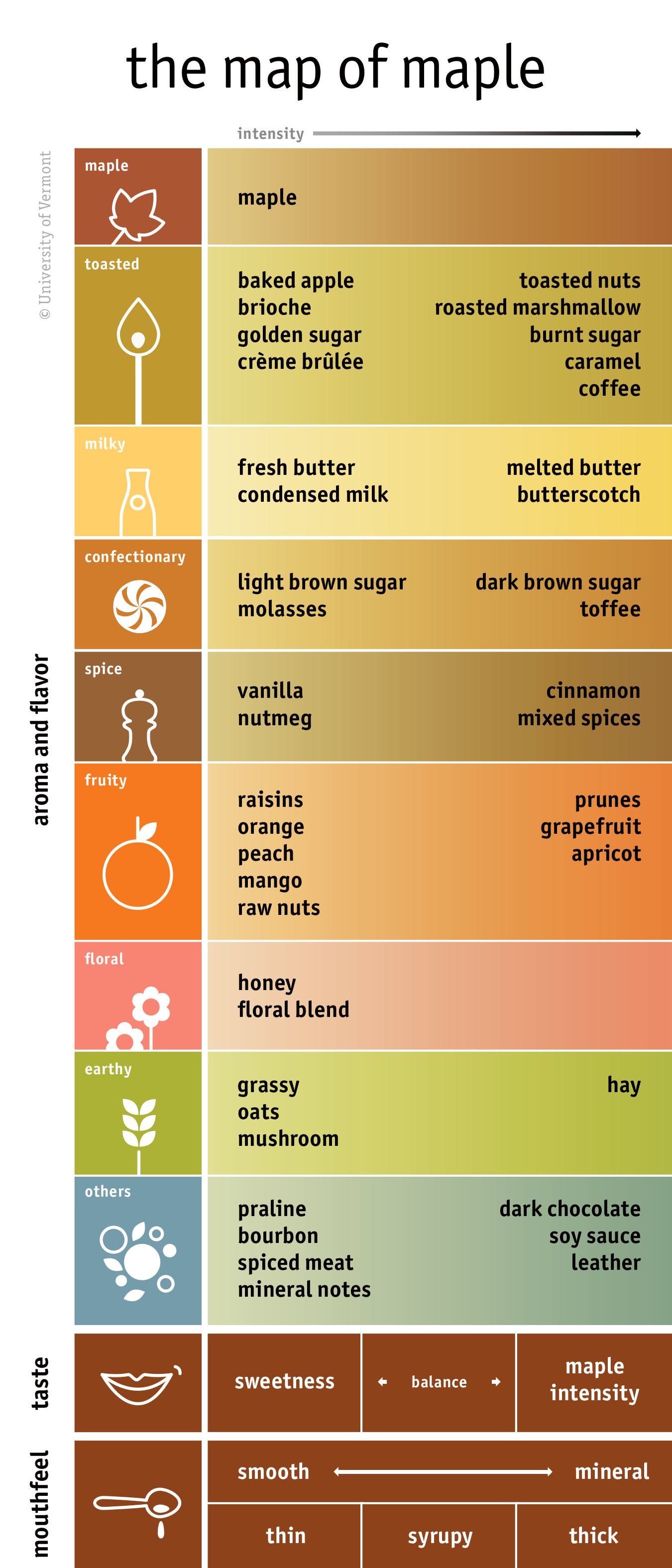

Within each color, some syrup is definitely more delicious than other and the flavors vary. The syrup of one producer near me always has a distinct vanilla quality. A dozen years ago, Vermont researchers focused on taste and created a “map of maple.” To give an idea, some of the more delicate flavors you might find are raw nuts, butter, honey, floral blend, bourbon, or cinnamon. Darker, stronger syrup might have caramel, toffee, toasted nuts, chocolate, molasses, even soy sauce. Canada has its own Flavour Wheel for Maple Products, prepared by the Centre ACER in Quebec and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and it has a somewhat different take. I exchanged emails with Nathalie Martin, a chemist at the Centre ACER, who clarified some technical aspects of maple flavor. She told me that flavor differences result more from the expertise and equipment of the producer than from the terroir. “This is despite the fact that research has shown that there can be differences in sap composition depending on the type of soil in the sugarbush.” People who really know the taste of a specific food or drink sometimes have an unexpected point of view. I was thinking of some of the delicate flavors I’ve just mentioned when I asked Martin whether there was a particular flavor she liked to find in maple syrup. “Personally, I like a slight woody note in my maple syrup, but it’s a matter of taste,” she said.

The sap, as it flows from the tree, contains roughly 2 percent sugar. Boiling, commonly aided now by reverse osmosis, raises that to 66 to 68.9 percent. Those are the US and Canadian required minimum and maximum amounts, measured in degrees Brix. There’s a practical logic to them. A less sugary syrup could ferment, and a more sugary one will more readily form crystals in its container. One other thing: the minimum sugar in Vermont is just little higher than anywhere else, 66.9 degrees Brix. If Vermont’s syrup is sometimes better, that could be because of a slightly heavier body and a little extra concentration of flavor.

Syrup can have defects. They’re rare in anything for sale, but they’re interesting because they underline just what a seasonal product maple is. As points of reference, producers can get kits with small bottles of syrup with each of the three most common natural defects. The off-putting, sometimes cardboardy one called “metabolism” tends to show up early in the season; it might be associated with deep winter freezes or, another speculation, with quick changes in temperature. “Sour sap” comes from letting sap sit at warm temperatures, so that acid-producing bacteria go to work. “Buddy,” triggered by too many warm days, appears toward the end of the run, when the buds are about to open. It’s often compared with the flavor of Tootsie Rolls. A few years ago, researchers at the Centre ACER identified a chemical marker for the flavor, the sulfur compound dimethyl disulfide. It isn’t necessarily the source of the flavor, but the more there is, the more buddy the syrup.

I once bought syrup that I thought had either a buddy or metabolism off-flavor and mentioned it to the producer. He tasted the syrup and couldn’t find anything wrong. I was just learning about maple flavor, and I wasn’t sure of myself, so I sent a sample to the Proctor Maple Research Center at the University of Vermont. A specialist told me over the phone, “Nobody could find anything negative to say about the syrup”; there was “no metabolism whatsoever.”

The prime Vermont expert in flavor was then and probably still is Henry Marckres, a significant figure in the maple world who has tasted syrup in every maple-producing state and four provinces. (In 2016, he was inducted into the North American Maple Hall of Fame.) Marckres, before he retired, was Consumer Protection Chief for the State of Vermont. A maple producer once described him to me as “a maple policeman,” though he’s actually friendly and accessible. I mailed Marckres a sample, too. “The syrup you sent me indeed had what we would call a metabolism off-flavor,” he responded by letter. “There is a slight odor that might be characterized as ‘woody.’ There is no maple flavor and the aftertaste is, to me, cardboardlike.” One of his colleagues, he said, considered metabolism to be like popcorn; it’s also compared with peanut butter. Marckres followed up by email: “Tasting syrup as much as I have over the past nearly 30 years allows me the ability to detect certain off flavors that others may not pick up at first.” I was relieved to know I wasn’t bothering people over nothing, but I don’t think I ever told the producer. And I’ve never since come across syrup with a flavor defect.

When you’re buying syrup, it’s much less expensive to go for a whole gallon. As time passes, crystals form in the bottom of it or any size container. When a piece comes loose, it’s colorless and looks like rock candy. Not many organisms will tolerate the high-sugar environment of maple syrup, but they do exist, and after you open a container, it’s important to keep it refrigerated. The syrup will last a long time.

Unsweetened Apple Pie with Maple Meringue Sauce

This apple pie with maple sauce appears in Vermont Maple Recipes by Mary Pearl, a spiral-bound book that she apparently self-published in 1952. She describes it as “one of the oldest maple recipes.” From one perspective, the sauce is marshmallow; from another, almost Italian meringue. Exceptionally for Vermont, the pie has only a top crust. I like a butter crust, but pie crusts in Vermont were always made with lard, and the quality makes a difference. My wife’s grandmother rendered her own; she used only lard in her crusts, and she baked a lot of pies, never just one. Tart apples are essential.

900 gr (2 pounds) tart but ripe apples, peeled, cored, and sliced

dough to make one 25-cm (10-inch) flaky crust

250 ml (1 cup) maple syrup

2 whites from large eggs, at room temperature

a fat pinch of cream of tartar, if you use a noncopper bowl

Heat the oven to 190° C (375° F). Arrange the sliced apples in a 25-cm (10-inch) metal or ceramic pie plate, deep enough that the fruit won’t boil over. Roll out the pastry and cover the apples with it, trimming and forming a neat edge, pressing to seal it to the pan, and cutting slits for steam. Bake until the apples are soft and the crust is brown, about 40 minutes.

Over medium-high heat, boil the syrup — which will foam up, so use a larger pan than you may think you need — until it forms a fine thread when poured from a spoon, about 10 minutes. Don’t let it go any further, or you’ll have pieces of candy in the sauce. Promptly take the pot from the flame and keep it warm near the stove. Whisk the egg whites until they just form stiff peaks, either in a copper bowl (freshly cleaned with lemon juice or vinegar and salt, rinsed, and dried) or else in a noncopper bowl, adding the cream of tartar. Then add the syrup in a thin stream while continuing to beat. When the syrup is fully incorporated, the meringue sauce will be thick but flowing. Serve it with the warm pie. Makes 1 pie and a lot of sauce.

Great piece, Ed Behr! Thank you for all that maple lore. One thing you didn't mention (or if you did it skipped past me) but I'm hearing more and more often is a preference for syrup produced the old-fashioned way over wood fires. I have a jug of Vermont syrup brought to me last summer by François de Melogue, that is made the traditional way at Fleury's Maple Hill Farm in Richford. It is dark and deliciously complex and, though I say it as shouldn't, it is superior to what I have been getting in Maine, as fine as that is. Do you know it?

Fascinating! I didn’t know much about maple syrup before reading your splendid piece. I’ll be making that pie recipe pronto!